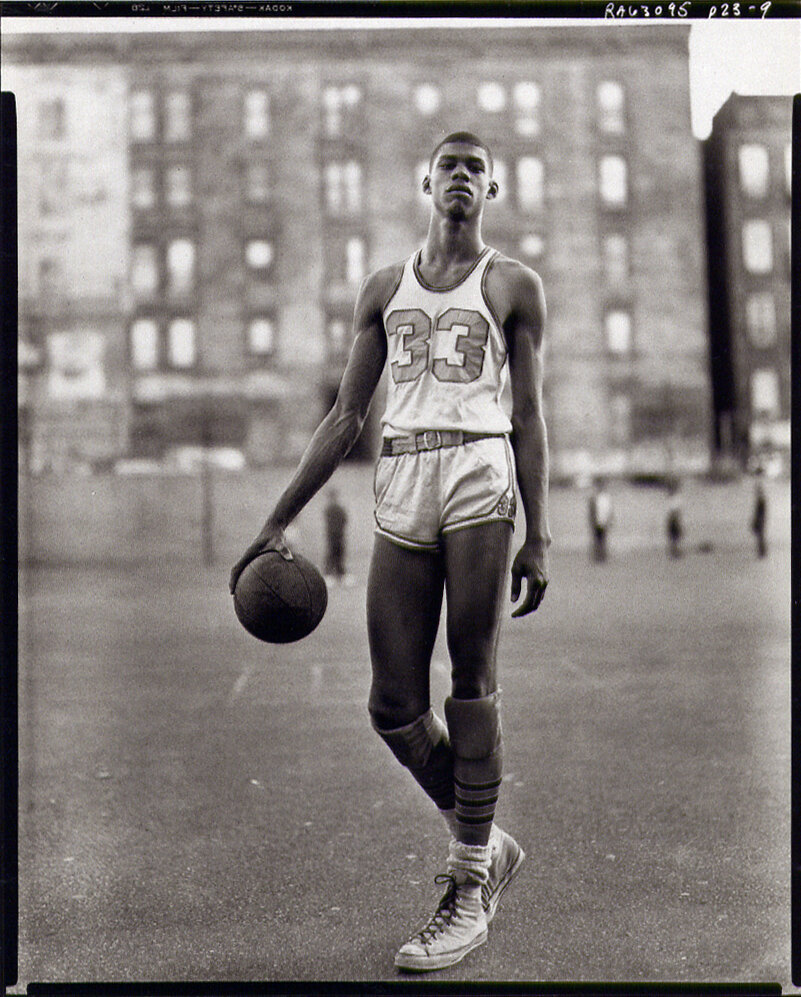

A key driver for my career were those that came before me. Over the years I have been exposed to masters who have followed their vision and achieved greatness in design, in business and in sports. Their work remains important; based in the past, yet still informing the present, and the future. They threw a spotlight on the importance of shaping things that are authentic and timeless.

Image by Agenda Brown at visualmarvelry.com

My Family, My Foundation

I was born into a multicultural, multilingual family; my mother is German, my father is American. I carry both passports. We lived in Austria where my four siblings were born, and Zaire, where I was born before moving to the United States. German was spoken in the home and we traveled there frequently, visiting with relatives. My parents stressed education and cultural awareness as a foundation from which to follow our own interests.

Photo - That’s me in my mother’s arms, the youngest of five children.

Love of Sport

I grew up loving sports and playing almost all of them. I was drawn to non-traditional sports, partly because they were available to me, as I grew up in an affluent setting, but also because I was keen on breaking the mold; doing what I wanted to do, or what interested me, and not what others expected me to do or…or not. I told myself I could ski for the Zaire Olympic team some day. Alongside doing the sports, I loved the equipment. The more specialized the better. My first pair of sport specific shoes were Spotbilt Juicemobiles. I would later work for the company that produced them. Part of the draw for me was the athlete endorsement by O.J. Simpson. I believed that having these shoes could make me run as fast as he did. I would later shape experiences just like this one through the products I designed and the brands for which I worked.

Photo - Skiing with my mates in Massachusetts.

Love of Gear

The sport I wanted to play the most as a young athlete was American football. What I lacked in size I made up for in toughness. I was pretty good until I stopped growing. While I loved the sport I didn’t make the basketball team. I was terrible. At tryouts for the Freshman lacrosse team coach asked if anyone wanted to play goalie? I looked left and right and saw no hands raised. So I raised mine. But it wasn’t a mistake that I wound up in the starting position. Lacrosse was the sport I played best. Height was not essential. Good eyesight, reaction time and willingness to stop a dense rubber ball shot at 80mph with your body counted. Everything about the equipment was different. The helmet, stick and gloves were uniquely purpose-built. I loved the “fastest game on two feet” and the gear required to play it.

Photo - Concord-Carlisle High School Junior Varsity Lacrosse.

My Road to Design

The road towards my future career began with the discovery of what I was not going to be. My parents never projected their own ideas or aspirations on to their kids. Our individual destinations were to be decided by being open to inspiration along the journey. It’s an approach that informs my work to this day.

As the youngest, I was open to the influences of my older siblings. The eldest joined the US Army, straight out of high school. The next in line went on to study civil engineering. I took the Army recruiting exam and I was told I could do anything I wanted in the army. I discovered later that this wasn’t quite true, but for a moment I saw myself flying helicopters. Failing physics and calculus courses, however, kept at bay any dreams I might have had about following in either brother’s footsteps.

My discovery of design was nothing short of a serendipitous event. Visiting my brother at Carnegie Mellon for his graduation, we came across a gallery space exhibiting the final degree projects from the Senior Design class. I saw color, typography, paper modelling and messaging; thoughtful and creative ways to communicate, where the visual was just as important as the verbal. There was no deliberation, no decision to be made. Just an automatic realization of the path I was meant to follow, and the world-class school that would make it happen.

Photo - Self portrait in the design studio in Baker Hall at Carnegie Mellon.

Design Yoda

Design education at Carnegie Mellon included both 2D and 3D studies, graphic and industrial design. We were taught by the best in every field and I enjoyed it all, but I was most intrigued by learning about materials and shaping things. I loved typography, shapes, color and layout, but was more excited by sourcing material and turning it into something useful, simple and emotional.

There is one professor whom I hold truly responsible for helping me to discover my inner designer. Steve Stadelmeier, my design Yoda, and we’re still in touch today. He taught me reverence for the power of design; for the ability of an individual to be thoughtful and intelligent in shaping the world and what we decide to put in it. The smartest person in the room, in a good way. He could tell the make-up of a plastic, just by smelling it.

Photo - Stephen Stadelmeier, Associate Professor, Associate Head - Carnegie Mellon School of Design.

Less Is More

Design education at Carnegie Mellon included art history. Monet, Giacometti, Brancusi, Picasso, Wyeth, Hockney, Duchamp, O’Keefe, Rodin, Ramos and Warhol opened up a new and exciting visual world for me. I learnt about the important schools, styles and movements of the art world, and also the ‘story behind the story’ of art, artists and the context in which they created.

A study of design history inspired my own collection of design artefacts, which today amounts to the Charliehaus Museum. I learnt about the incomparable Charles and Ray Eames and Dieter Rams, whom I would later meet in Germany. ‘Less is more’ became the gospel. But it was The Bauhaus that cast the ultimate spell. A complete gamechanger, it’s the era, and the movement, that has been most influential for me, my life and my work as a designer.

Photo by Charles Johnson - Student Dormitory building, The Bauhaus, Dessau.

History aside, I was also equally inspired by the contemporary. The Macintosh was launched during my second year at university. Three decades later I would work for the first sports brand to connect a shoe with a computer; the Apple IIe. While Carnegie Mellon was already a computer science powerhouse, design and computing was still in its infancy. The school knew computers would be a powerful tool for designers, but none existed yet. Still they wanted to arm us with the tools that were available and made programming in Pascal mandatory. While I have never written a line of code since, I grasped the invaluable knowledge that complex problems can be solved using binary code. That’s a beautiful reality.

The Carnegie Mellon approach was unique in that it prepared us to be designers who could solve real-world problems within the context of specific materials and manufacturing, rather than design for design’s sake. It has proved to be an invaluable foundation for every angle, and era, of my career, past present and future.

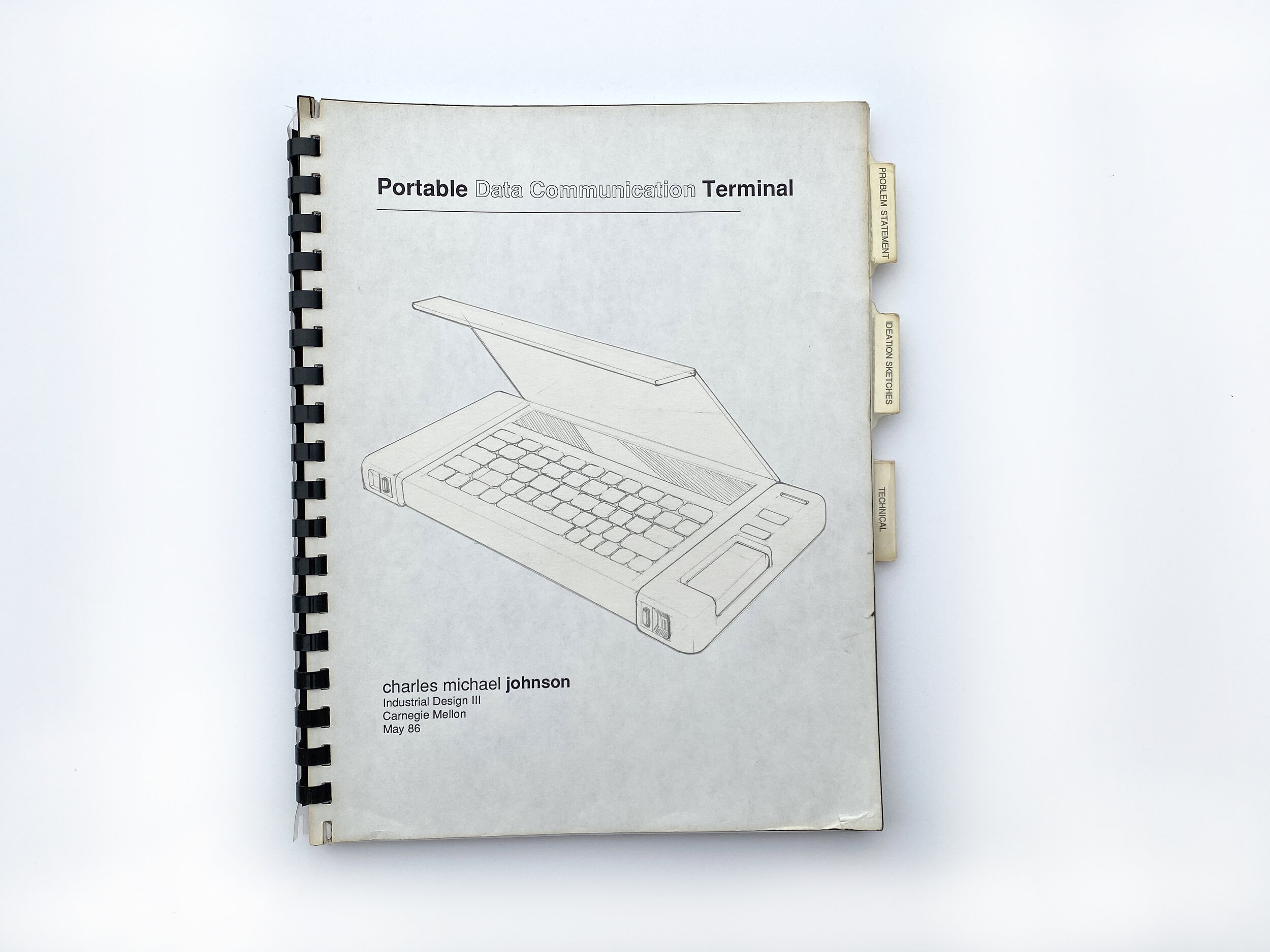

I graduated from university having received the IDSA Merit Award for my graduating class. The award recognizes ‘exceptional student design talent’, highlighting ‘the very best creativity, problem-solving and design brilliance.’

Armed with award-winning confidence and a portfolio I made my way to New York.

Photo - Project Book, Portable Data Communication Terminal.

Designing With Tech

From Circuit Boards to Sneakers

My fate to be a designer was sealed with my first role at Hyde Athletic, a sports company outside of Boston, that manufactured products like skateboards and cleats. It was the chance I’d been looking for to combine design and sports. Hyde owned two footwear brands, including Saucony and Spotbilt. I found myself designing basketball and running shoes in the shoe-making capital of America at a time when the industry was still grounded in skilled craftsmanship. I learnt about materials, pattern making and prototyping, which meant I could see my designs evaluated and realized for final manufacturing.

One day at the studio I saw a pair of shoes unlike anything I had seen before: PF Flyers mid-cut olive canvas sports shoes with a molded rubber bottom that wrapped up over the toe, giving it a bold and protective look. The molded bottom had an undercut that until then was a no-go for anyone who knew anything about production molds. Achieving that was super-exciting to me, and it gave the shoe a unique character.

Photo - Early basketball shoe design concept sketch.

Photo - With Jules DiTirro.

At Hyde, I was introduced to Rob Strasser and Peter Moore, two legends who would have a massive impact on my career. I learnt quickly how to design footwear, well, alongside four other designers, including Jules DiTirro, formerly of Nike, who became my mentor. I devoured all the legendary stories that had shaped the Nike brand and approach. That was the time that Nike had launched the Air Jordan shoe, changing the industry forever. I knew I needed to move forward in this direction.

My Harlem Renaissance

I was next recruited to work at Adidas USA in New Jersey, a stone’s throw from New York City and my first step towards design on a global scale. I traveled to Korea to develop product directly with factories. The dawn of manufacturing and marketing modern footwear was in full swing. My experience of life in NYC served me well, inspiring a new-found connection to black culture and its music, fashion and pride. I became immersed in the culture for which the lion’s share of the product we designed was made and sold. But business for Adidas at the time was not strong and the company was forced to make cuts. Fortunately, I was recruited for a position at Avia (owned by Reebok at the time) in Portland. Having traveled frequently during my childhood, I was very open to experiencing something new: the Wild West. The culture could not have been more different.

Image - Footwear News commissioned sports brands to submit their view on the future of sports equipment. This rendering was my vision of what tennis would look like ten years in the future.

Portland Or Bust

What Portland lacked in cosmopolitan atmosphere it made up for with its independence of spirit. The culture was very much ‘outdoor’. Whilst I was still enjoying designing footwear, it was clear Avia was not going to grow exponentially, so I kept my eyes open for the next step on my journey.

Meanwhile, Adidas was going through an amazing transformation, with Rob Strasser and Peter Moore now behind the wheel with a remit to reinvent the brand. At Nike they had been responsible for its emergence as an irreverent, innovative sports brand that converted both the performance and emotions of athletes into hugely successful products, like Air Jordan. Their relationship was built on a like-minded vision, a ‘fuck-you’ attitude and trust in each other’s expertise. They left Nike and formed Sports Incorporated and set up office in Southeast Portland. Before I left Adidas in New Jersey I had made contact with another important design mentor, Jacques Chassaing, who had transferred to Adidas in Germany, and we talked about the possibility of me working across The Pond.

Photo - Jacques Chassaing in his office at Adidas Headquarters in Herzogenaurach, Germany.

In the design studio at adidas headquarters, Herzogenaurach, Germany.

The Purity

of Performance

I reached out to Sports Inc. and they shared with me their new product strategy: Adidas Equipment. ‘Everything that is essential. And nothing that is not.’ This approach achieved two things. First, it reclaimed the Adidas brand as the equipment manager to the world; the three stripes once again would become a key performance element. Second, it was an overt counter to Nike’s flashy character. It was the newest, most on-brand, focused strategy I had ever seen. I was offered a role at Adidas HQ in Herzogenaurach, Germany, in the Advanced Product Group (APG), a team of sport-focused designers, pattern makers and developers working on the most advanced product concepts. My focus was designing for the Equipment collection, a mix of basketball, running, tennis and outdoor footwear. I learnt about how the harmony among design, function and manufacturability can create a timeless product. This was accompanied by frequent visits to the Adidas archive, which had curated legendary pieces, such as Jesse Owens’s track spikes, Franz Beckenbauer’s football boots and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s basketball shoes. They served as reminders of what made the brand unique and helped the best athletes in the world perform at the highest level.

Photo - Spread from the first Adidas Equipment collection catalog.

What I came to realise when I arrived in Germany was that I was the only trained product designer at Adidas Headquarters. Until that point the people responsible for creating product were pattern makers. The focus was creating three-dimensional form from two-dimensional parts in a way that was easy to manufacture. The good designers understood the importance of creating a form that both fit and looked beautiful. Draftsmen created the technical drawings for the bottoms of the shoe. Neither were skilled in shaping the complete product. Except for Jacques. He understood pattern making, mold technology and he could draw. For the first time I was exposed to industry-leading sport scientists who did research in biomechanics and athlete performance. I developed a passion and a knack for converting their lab-oriented data into product benefits that shaped my designs. For example, the discovery that a traditional shoe sole inhibits the natural side-to-side flexibility of the foot; I designed an outsole to include a groove that ran from the toe, straight through to the heel. This brought a never-before-seen, unique character and benefit.

Photo - My colleague, pattern engineer Raoul Lemos at his desk across from mine at Adidas Headquarters in Herzogenaurach, Germany. My design drawings are on the wall behind him. His work was to convert them into the two-dimensional patterns that would be used to produce the shoe.

The Equipment Tennis Lite with its unique longitudinal flex groove.

Everything That Is Essential

And Nothing That Is Not

Peter Moore taught me that, while it’s important to know what came before you, in order to be innovative, you have to think differently, have a vision of what will be, and follow it. What he created in Adidas Equipment was just that; it went completely against what was occurring in the market. The signature color green for the first Equipment collection was initially not well received by retailers. Peter had no problem telling them to “Fuck off. This is the color.” Thirty years later the shoes remain on the market.

Conceptualization of the Equipment collection was genius. It reclaimed the legacy of the brand, positioning founder Adi Dassler, as the equipment manager to the world. Product was defined by essential needs for functional performance. It exploited the purity of German design and defined a clear and simple approach, counter to industry standard at the time.

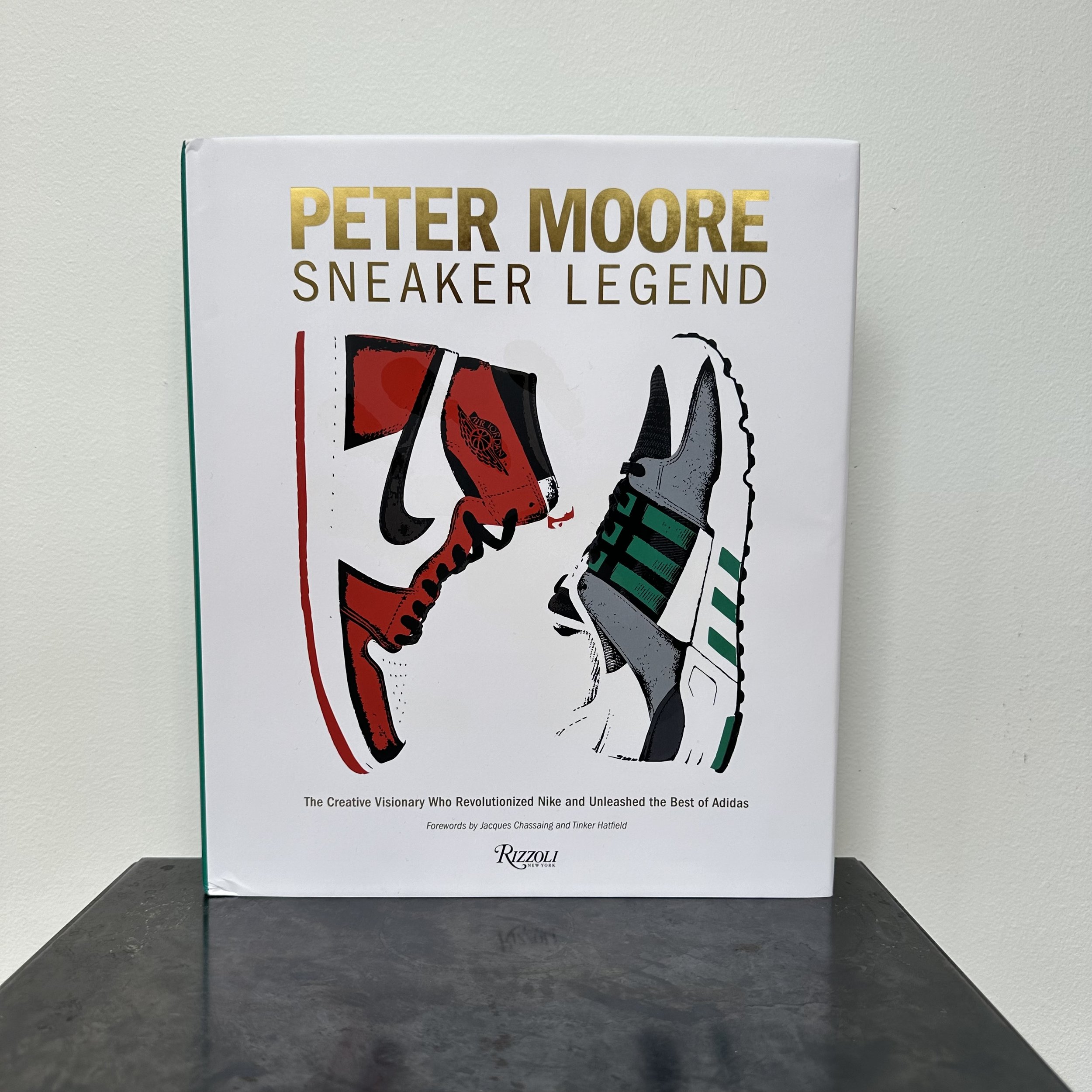

Photo - Peter Moore

Peter Moore died in 2022. I was honoured to have been interviewed for and to have some of the work that I did under his leadership included in the book the paid homage to him and his work, Peter Moore Sneaker Legend.

When and how did you meet Peter? Share memories and stories, and esp projects, products (e.g. Kobe) you have worked with Peter What did you learn from Peter? What do you miss the most?

I first met Peter around 1987. I was working at Hyde Athletic at the time; my first job in the industry. Hyde owned the brands Saucony, Spotbilt and

PF Flyer. One day I saw a sample in the conference room. It was like no other shoe I had seen before. It was a PF Flyer branded shoe that had a rubber toe wrap that came up from the outsole as one piece. Until then that was something seemingly impossible to achieve with existing molding methods.

I asked the President, John Fisher where it came from. Some time later John pulled me into the conference room and said, “You were asking where that shoe came from? These are the guys who did it.” It was Rob and Peter. That was when I met him but there was no real exchange. Rob was more communicative at that time. But what resonated with me was potent. Peter had tapped into the most advanced molding technique in the industry (at the time that was Italian manufacturers) to create a shoe that had totally unique functionality and from it created an iconic looking shoe. (Years later that look would find its way into the first Equipment Adventure shoe.) That’s when I learned, point blank - form follows function in footwear.

I went on to work at Adidas USA in New Jersey. It was during that time that I met Jacques Chassaing through meetings I attended at HQ in Germany. Jacques and I hit it off; I think I represented a new breed of footwear designer classically trained in industrial design that he sought. He talked about me coming there to work. But shortly after I was recruited away from adidas to Avia, a Reebok-owned company based in Portland. In the end I didn’t really like the job, the company, it was too hamstrung by Reebok. But in Portland I got wind that Sports Inc. got adidas as a client. I was such an eager beaver

I contacted Sports Inc. and that was the second time I met Peter. This time we spoke; he took me through the Equipment concept, he told me about the ties to Germany and he sent me home with a catalog. I fell in love with the product but even more so the direction that he was taking the brand. I called Jacques and asked, “Remember you mentioned a job in Germany? Does the offer still stand?”

So in 1990 I moved to Herzogenaurach to join Jacques and his newly formed Advanced Product Group (APG) working on Equipment. Rob was in Herzo but Peter stayed in Portland. He would send over these large format boards with his concept renderings. That was his way of communicating his vision and we were meant to take the vision and interpret it, push it forward. He was clear in his guidance but also gave us a certain freedom.

He designed the first Streetball shoe. I took that foundation and designed Streetball 2. It was the same but also different if you know what I mean.

I learned from him how to establish a creative direction from which creatives could work. And not just footwear but also apparel. Massimo Vignelli said, “If you can design one thing, you can design everything.” That was Peter.

I left Adidas; I was recruited to work for Converse out of New York City. They were based in Boston. That job lasted a couple of years, then I opened

up my own design studio that I named Sports Creative, an unabashed nod to Rob and Peter. I think around that time Peter’s book came out and Owen sent me a copy. It came with a note from Peter in which he wrote that he found the older he got the more creative he got. I remember how uplifting that was. It said to me that there would always space for good design; good design is timeless even in its creation. Peter used to say the moment that you talk about design in the context of trend it’s over. That resonated with me. It taught me to follow your instincts. What’s right is right and it always will be.

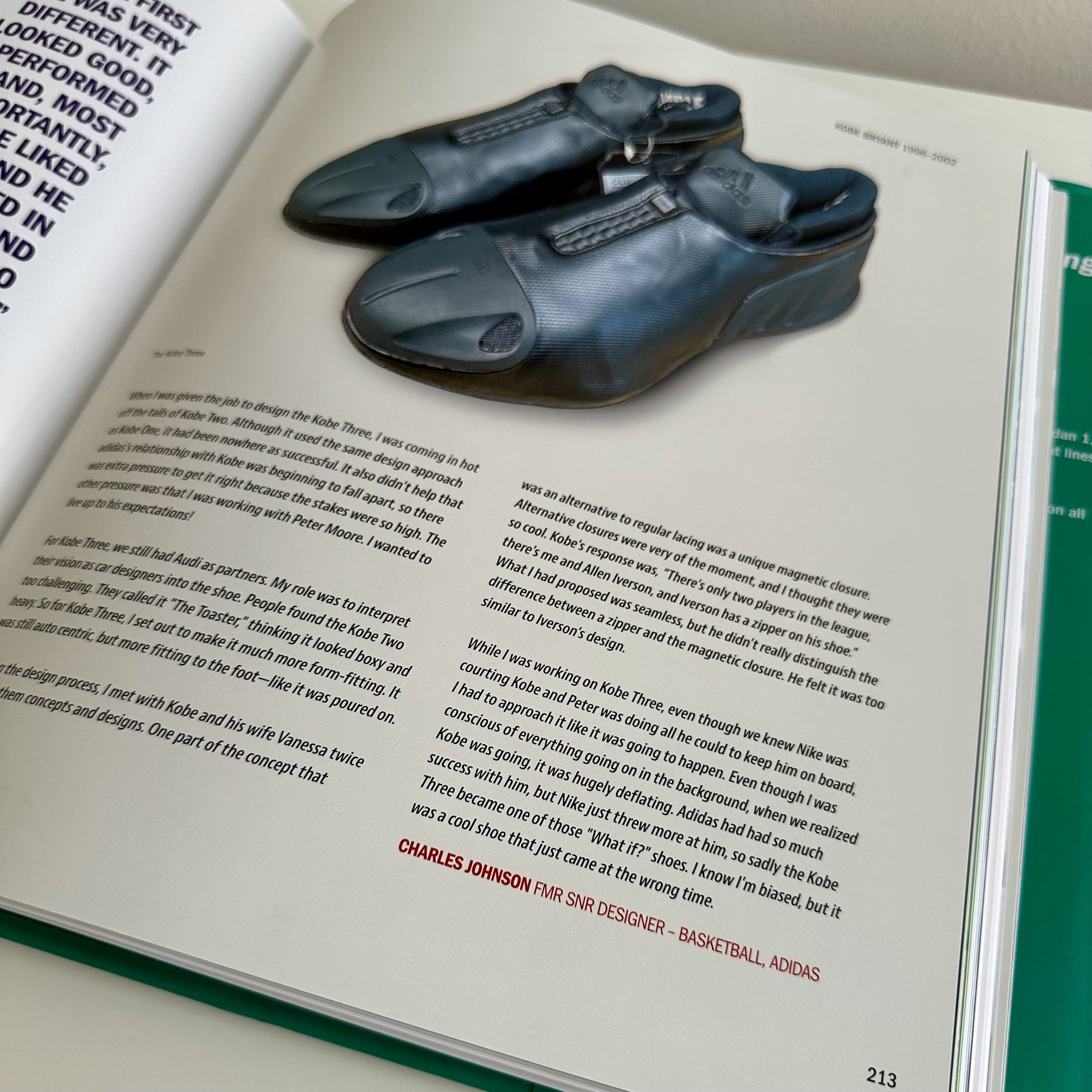

In any case having my own studio was great. I did well but I missed the fight; being a part of a team trying to beat a rival. I made contact with adidas who I learned was looking for a Senior Designer for Basketball. So I went back to Portland. It was then that I worked closely with Peter on the Kobe 3 shoe. I remember he and I traveling to LA to meet with Kobe to present the design. We traveled to Herzo as well to present to Herbert Heiner. We brought the big boards.

What I miss most is the beacon that Peter was; the north star that was there to follow, to aspire to. He represented a simplicity and clarity that no-one since has been able to represent for me in my design life. No bullshit.

He’s gone but at the same time he remains present. All of us who have worked under him have that I believe. We are trying to channel in our own ways and paths, what he did so well. And we’re all proud of to have worked with him; honoured that we had the opportunity….because he was one-of-a-kind. As I said in my tribute message to him, Peter has everything to do with the designer that I am today.

Grand Slam Designing

One of the first assignments I got when I arrived at Adidas in Herzogenaurach was to support the footwear needs of Grand Slam Tennis Champion Steffi Graf. For me it was the first of what could be considered a signature shoe. Under the tutelage of Jacques Chaissang, the shoe was based on the Grand Slam which he had designed. Textile stripes lightened it up a bit. A three stripe torsion bar in the sole gave it a new 360 degree functionality. I never met Steffi, I was only able to watch her practice. Later it was a thrill to see her play in the most important tournaments in the world in shoes that I designed.

Hey CJ!

Rob had set up office in Herzogenaurach. Peter would travel over from Portland to present his creative and product direction. I was a soldier in the fight and followed their intentions. Peter was a no-nonsense communicator and made things very clear. There were no politics, no bullshit and his ideas were easy to understand yet challenging in their simplicity. Rob was a larger than life (literally) character who valued every doer on the team. While he was at executive level, he never put on airs about that. After all he was a beer-drinking sports junkie (a very smart one) from Oregon who just happened to be on the Board of Directors. He stopped me once as I passed the door of his office and said, “Hey CJ, What do you think of this?” When I had a party at my flat in town, he came. That was Rob. The mindset that everyone is important, that everyone can have something to offer, which I learnt from my father, was reinforced by Rob.

Photo - Me with Rob Strasser at my home in Herzogenaurach, Germany.

Learning From

a Master

Jacques Chassaing was a pioneer. He was trained as a dress shoe designer, which put a high emphasis on form, comfort and detail. He was masterful at creating simple, pure designs.

He took this same approach when he transitioned to sports shoes at Adidas, adding on the functional integrity. With this toolbox he designed preeminent classics like the Grand Slam, Concord and Superstar models. Beyond his experience as a craftsman, he had an appreciation for design and innovation. He had a vision for how formal product design methodology could elevate footwear design.

Never before in the footwear industry had I encountered somebody who represented what he did. At long last I was encouraged to match my product designed trained ‘Less is more.’ approach to sport and performance.

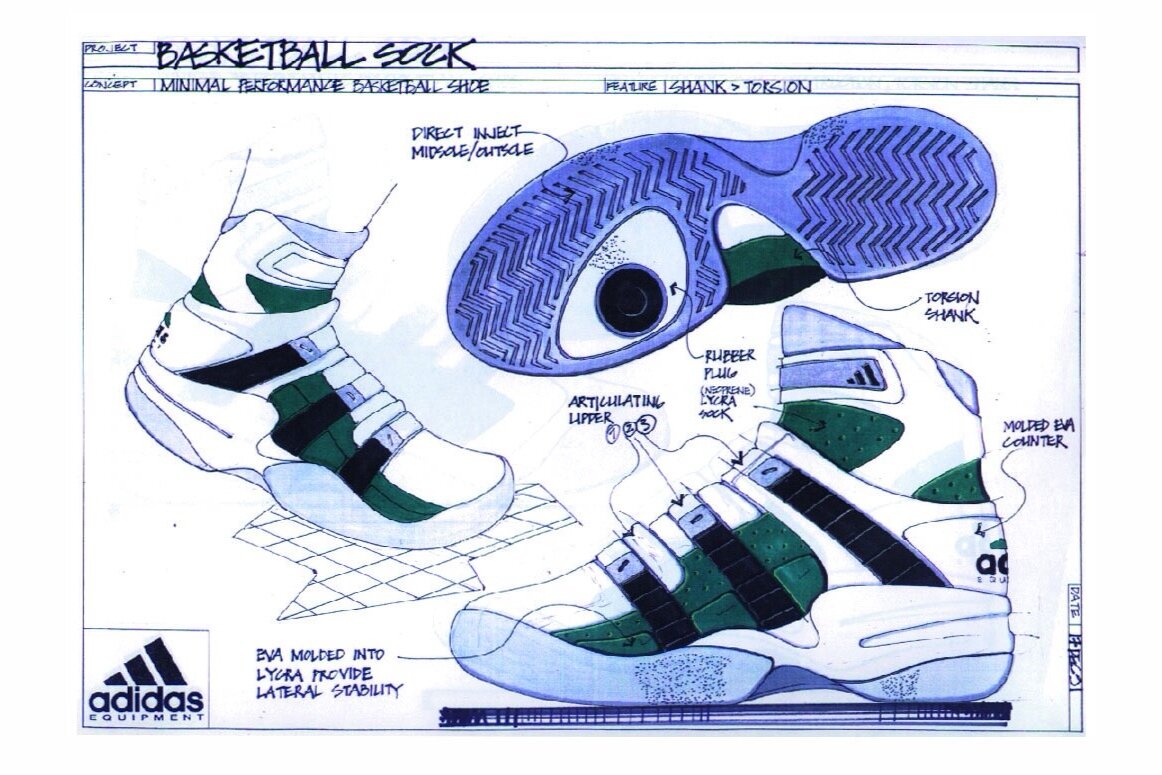

Sketch of the Adidas Equipment Basketball Sock.

Pumping Product

As part of the APG (Advanced Product Group) I was charged with converting research findings and industry-first technology into performance products. One of those technologies called Tubular allowed for pneumatic chambers to be integrated into the midsole of a running shoe. The chambers could be individual inflated with an onboard pump allowing a runner to tune their cushioning to their individual needs. Included in the chassis of the shoe was an LCD screen that showed the air pressure in each chamber.

Making News

The Tubular 4 made the cover of USA Today notable as the most expensive, commercially available sport shoe ever, at $200.

Technology Extension

We also developed Tubular technology as a two-chamber unit placed in the heel only. I designed a pneumatic pump (below) used to fill the chambers; a proud moment for me as it was the first non-footwear object that I designed as a professional.

The Wall

Adidas commissioned film maker David Lynch to tell the story of a runner who overcomes the proverbial wall with the help of Tubular technology.

Click the image to play video.

One for the Archives

In the past decade Adidas has worked to archive their product history of the past 70 years. In 2020 they produced this companion book; over 60 pages chronicling the most meaningful shoes in their archive.

I was thrilled to learn that one of the shoes that I designed, Streetball II was included.

This is the original sketch of the Streetball II basketball shoe. In 1990 it sold over 1 million pairs, a benchmark at the time for excellent sales performance.

NYC Calling

My next opportunity knocked with a proposition to return to the US and take up a design position for Converse in New York City. I would open a satellite studio, absorb the trends and convert those into product concepts. The remit was a designer’s dream: design independence in one of the greatest cities in the world. I settled near Union Square and spent my days trend spotting and taking photographs of urban fashion, creating designs based on what I saw. After two years exercising my independent creative muscle, I decided to put down some deeper roots in New York and open my own design consultancy, Sports Creative. My first client was Prince Tennis, which at the time was owned by Benetton Sports System. That contract kept the lights on. The idea that I could seek the work I was interested in and build my own business was thrilling. It was a grind, but it was my grind.

Photo - Converse Design Studio, New York City.

On Broadway

Sports Creative Group, Inc. was located at 1133 Broadway, three blocks north of the iconic Flatiron Building in Manhattan. I thought of New York as the best city in the world and was thrilled to be running my own business from an NYC address. It didn’t seem like work. I was having fun!

New and Natural

For 5 years I had established myself as a footwear designer. But I had aspirations to do more; to design things other than footwear. Founding Sports Creative was my opportunity to do so. My first client was Prince Tennis who commissioned me to design a new premium performance tennis shoe. That was accompanied by a new shoe box which took design cues from the Natural Foot Shape technology; it used raw or natural cardboard and perforations that mimicked the strings on a tennis racket.

Design Acceleration

Modern athletic footwear has come to function not just as foot covering but as transportation. So it is natural that designers took design cues from transportation vehicles. I was obsessed with motorcycles so they became natural references. Establishing a solid performance architecture afforded me the freedom to design a suite of details that borrowed from performance motorcycles. I race tire informed the outsole tread. The midsole took the form of a side cover. The lace system anchor looked like a subframe. The heel stabiliser took the finish like that of a carbon fiber exhaust. Lastly the “Flying P” logo looked like a motorycle brand.

Sneaker As Product

When I founded Sports Creative I was keen on establishing two things - first a full service studio that offered product, graphic and package design and second to bring notoriety to footwear design so that it would be seen in the same light as other product design categories. At the time, Graphis International was renowned for publishing the world’s most prestigious annuals with award-winning work from international talents in design. I was thrilled when not only one but two Sports Creative products were featured in their Product Design 2 Annual. To me that meant Sports Creative had arrived.

Photo - Killer Loop Outdoor Boot and Prince Tennis Shoe as seen in Graphis Product Design 2.

RL Likes

New York at the time was experiencing a fashion renaissance. Designers like Donna Karan and Calvin Klein were accepted as American designers who had reached the global stage, bringing simple aesthetics to the modern, fast-paced NY lifestyle. Part of that lifestyle was pounding the city’s pavements, so sneakers started to emerge in collections. But these designers lacked the expertise to design and develop athletic footwear. Ralph Lauren created an athletic apparel brand called RLX. As his collection always took a 360 approach, he wanted competent, robust footwear designs. I was brought in as a full-time consultant to design running, outdoor and luxury sport silhouettes. Working for Ralph meant a complete immersion in the brand. That was made easy because of his masterful storytelling capability, his obsession over detail and his mission to sell a lifestyle, not just ‘things’. The vision for his seasonal collections was embodied in the rigs that were shaped. Guided by Ralph, carefully curated installations complete with garments, accessories and other artefacts (a nautical collection included an old diving suit with metal helmet) set the stage for direction. Designers spent time with the rigs, shaping product that throughout the design season would replace the artefacts. As Ralph reviewed his designers’ work, the sign of approval was a small orange sticker with the expression ‘RL Likes’. If something was described as ‘deadly’, even better. My experience with Ralph taught me how to shape a vision and to romanticise it by creating a world that would embody the vision enabling others to create within the context of that vision.

Photo - One of the shoes I designed for the Ralph Lauren RLX collection.

The Inspiration

That Became

A Brand

Having my own business meant that alongside client work I could dedicate resources to follow my dreams and visions; like starting a brand. A series of inspiring moments and the right circumstances afforded me that very opportunity. Learn how Black Fives, the first ever black heritage inspired basketball brand was created.

Missing the War

1999 was the best year for Sports Creative. I was pleased with the success I had as a business owner and independent designer. I was winning the battle of maintaining a business, but I was missing the war. I missed competing with other companies and being part of a collective mission. I missed working for a brand. Adidas was calling.

By now Adidas had a large office in Portland and had gone through another era since I was in Germany. Rob Strasser had passed away unexpectedly and while the brand did experience success, a shift was occurring that needed new direction and leadership. I reached out to the Head of Design, with whom I had worked with at Avia. They needed a Senior Designer for basketball; one with management experience. I took the job. I was able to work on developing new technologies and high-profile projects such as the Kobe 3 basketball shoe, working again with Peter Moore.

Photo - Sports Creative vendor booth.

Kobe Three

I got some great assignments in my career as a footwear designer. One of them was working with Peter Moore and the Audi Design Studio in Los Angeles on the Kobe 3 basketball shoe. It was the third in a series that used the car design methodology of creating a form from clay and turning that into a shoe. It was the last shoe designed for Kobe before he left Adidas and went to Nike.

Photo - Kobe 3 sketches, model and final designs.

Reggie Bush Trainer

In 2006 Adidas signed Heisman Trophy winner Reggie Bush. He would be the marquis athlete representing the Adidas Training collection. The design I created for him considered his super-human motions on the field; the shoe kept him planted during extreme cutting while maintaining minimum weight during leaps over other players on the field which he was known to do.

Photo - sketches for the RB619 Training shoe. Final shoe below.

Strategy

The Adidas brand and I evolved in tandem. By 2007 I was working for the Director of Design, helping to shape product strategies. The work was fulfilling and tapped into the capacity I had to shape things beyond the drawing board. I was creating guidance for others to follow, not only in the product arena, but also in operations and brand education. But there was a limit to the level that I could reach. A call from a recruiter boasted a design leadership position for Crocs, based in Italy. I had harboured a dream to live there, but when speaking to them, I determined that what they needed was not a Design Director in Italy, but a Creative Director at HQ. While I was talking myself out of the dream job in Italy, I saw the opportunity to have the influence and input I craved.

Photo - Select images from Adidas Design 101 guide.

Form Follows [fun]ction

As Creative Director I inspired the design team, and also was unable to draw the leadership towards a new way of working. Crocs was built on the success of one shoe. A few followup success established them as a potential growth brand. When I arrived I guided the brand to look beyond the success of one item, to understand how design shapes vision and product and how to establish brand identity. My first initiative was to shape the visual language for the brand which ensured that both the product as well as the look and feel of the brand was authentic and consistent. Tools were created to guide both internal as well as external creatives.

Herzo Calling…Again

The mark of a good recruiter is to find you when you’re not looking. I had spoken to no one about the challenges I found at the chaotic Crocs, but still I got a call about a job; one for which I would have to relocate back to Europe. I was more than ready. Puma was looking for a Head of Footwear Design at HQ in Herzogenaurach, Germany. I knew it was my job. The icing on the cake was their Motorsport division, a partnership with Ducati, and a line of motorcycle boots. Building and racing bikes had long been a passion. To be able to incorporate this into my work was beyond a perfect fit. I joined Puma in 2010 at a time when they were on the backside of record success from the creation of the Sportstyle segment of footwear, a hybrid of performance sports and fashion. The brand had many collaborations with external designers and brands, with a high emphasis on design. Yet the brand needed a reboot and shortly after I arrived, the CEO, Jochen Zeitz, the mastermind behind the success of the 1990s, left the building. The battle to recover success was on.

By then I had designed virtually every form of mainstream, sport-specific footwear, except football (soccer) boots. I had to gain credibility in what I was doing and this was an area where I had work to do. I went straight to my comfort zone: research. From there I developed a revolutionary boot that was grounded in the knowledge that the most power a player could deliver to a football was with the bare foot: EvoPower.

Photo by Frank Busch - In my office at Puma Headquarters in Herzogenaurach, Germany.

Forever Faster

Puma had an innovation team focused on developing new concepts in sport performance, new manufacturing and materials. They were a solid team of industry experts but had no recent success and little exposure across the brand. And… design was not part of the organization. Still, innovation was a legacy strength and there were expectations that it must contribute to projected growth. I forged a collaborative connection with the team. Being vocal with my ideas about how the team could be better leveraged, I was soon offered a role as Head of Innovation Design. Once there, I continued to embrace research and developed new technologies and concepts. The Director of Innovation at the time was based in Puma’s Boston office. I proposed to the CEO that I take on leadership of the team and he accepted. In 2015 I was appointed Global Director of Innovation.

Photo - Puma Innovation, Herzogenaurach, Germany.

Vision Making

The team had been operating under the same modus operandi for decades. A shake-up was overdue. With the support of strategic design veteran, Karen Reuther I set about establishing principles to guide us all in our daily thinking and approach. In order to know where you’re going, you need to know where you have been. A ‘Culture of Firsts’ emerged as an hommage to Puma’s innovation legacy.

Next we created our innovation ethos: Athletes Rule, Push Limits, Visualize the Future, Explore Extremes and Smash Barriers. When we communicated our work outwardly, we addressed both science and emotion; the notion that it is not only important how a thing works, but also how it resonates with the user.

Another legacy I inherited was the perception (and to some degree the reality) that the innovation team was not transparent enough, nor did it deliver consistently. I set out to stage events to showcase the many opportunities we shaped and the attention we gave to all of our businesses. I also created a collaborative process where stakeholders could offer clear and direct feedback. While it was a first-ever moment and our efforts shined, it overwhelmed our audience and it came across as an innovation market, rather than a guiding event, which is also what I intended. I decided that rather than leaving it up to the audience to decide the vision, we take positions and lead the audience by shaping visions of our own. That culminated in 2017 with the Innovation Vision Summit, which showcased a complete range of concepts in product, materials, manufacturing and design. It was an overt attempt to transition from ‘order-taking’ to ‘vision-shaping’.

Connecting

the Dots

In my experience I know that if something is innovative, it challenges at least one, sometimes several norms. The good news is that if it challenges something, then you know you’re on to something new. The process can be complicated; one that requires channeling varied components and fulfilling numerous needs. But this challenging environment is motivating. The bad news is that people resist the new. So successful innovation efforts require making the complex simple; connecting the dots to align toward a vision. It also means navigating an inherently resistant landscape with the mission to minimise discomfort, so that the customer can feel comfortable enough to buy. It became essential to me as a leader to develop the skill to connect the dots and to lobby stakeholders so that they could be comfortable buying in.

Photo - Puma Innovation Summit.

Best Year Ever

The list of innovations that I directed includes: Ignite, EvoPower, Triaxial Weave, EvoDisc, EvoKnit, Thermo R Vent, NRGY, Hybrid Foam, Jamming, Netfit, FuseFit, AutoDisc, Pumatrac App, Fit Intelligence and Xetic. In more recent years I pioneered connected technology and experiences such as the Pumatrac App, Fit Intelligence, as well as Esport/gaming offerings, such as the Puma Playseat and Active Gaming Footwear. Not all of these innovations were highly commercial. Still the work that I directed in my five years as Global Director of Innovation at Puma tracked with the steady growth of the business, which contributed to Puma’s best year ever in 2019. This is the power that solid, research-driven innovation can deliver. When I speak to people outside of the company, many are impressed with all that we have done. When they learn how few people achieved these results, they are even more impressed.

The Future Is Now

I am extremely proud of what I have accomplished throughout my career journey, in collaboration with so many excellent people, most notably in my ten years at Puma. However, the onset of the Coronavirus era will leave it, and many other companies, challenged by a traditional success formula; satiating consumer desire for products they don’t really need, and at record pace. This is proving to be a shallow pursuit and costing the livelihood of people at every point of the industry spectrum. What does this bode for the future? As designers and entrepreneurs, we have a responsibility to uncover what is truly meaningful for people, and how to supply it. If we pay attention to humanity and the environment, the road ahead becomes clear. Aspirations that aim higher than simply sustained dollar growth will inspire natural creativity for a truly valuable, common goal. Humanity. This is the aspiration that will shape my future.

Image by Agenda Brown at visualmarvelry.com